«Are you an aggressor? Are you part of the system of aggression? Are you both? We wanted everybody to question themselves in front of violence and, walking around the exhibition, within spectators’ discussions, you could hear the upheaval of so many consciences in search of answers». These are the words of Pau Garcia, founding partner of Domestic Data Streamers (DDS). The company usually collects data to be transformed into works of art with the aim of triggering debates on issues of social relevance. This idea inspired 730-hours of violence, an exhibition that took place in the Mutuo Gallery of Barcelona from 7 to 30 September 2021, for seven hundred and thirty hours. The project is one of the winners of European call MediaFutures that aims to promote ideas and artistic projects which explore data and new technologies, highlighting their impact on individuals and the community.

Read also: The Italian citizen attitude towards information – IPSOS Research

Nine installations were placed in the gallery, with which the public had the opportunity to discover how much violence is always present, around and within themselves. «Data is the language. Art is the way we engage. All our projects are born with a question that we try to answer in a collective way because we believe that in the debate new perspectives on the world arise».

What does violence look like? The question concerns the viewer as soon as he enters the exhibition. The work “Visual definition of violence” asks the public to select an image of what best defines brutality: explosions, weapons, quarrels, religion, murder, each choice is printed on a single tape that gradually fills with violent images. They begin to overlap to create a confused and indistinct agglomeration.

According to Pau Garcia, for most people violence is something physical and tangible. But this is not the most dangerous type. There is a systemic and pervasive violence that is not visible, cannot be indicated, circumscribed, faced». It is the “slow violence”, better exemplified in the so-called “fatbergs”, solid agglomerations of waste produced in the comfort of our homes.

The largest fatberg was found in London, weighed 130 kilograms and was 250 meters wide. Its components were traced by chemical analysis and brought before the eyes of spectators: glass jars placed on the wall, containing toilet paper, grease, cooking oil and other residues. «These are the many small actions of which it is difficult to identify the responsible, which settle in a single act of violence against the environment and society», comments Garcia.

Then there is a type of violence that we see every day: hate speech. “Nigga”, “whore” and “faggot” are the words contained in the tweets that the DDS team has downloaded for four months. Those insults were repeated a million and six hundred thousand times – reports Garcia -. Each of these corresponds to a blow of the hammer on the wall. We recreated the rhythm of hate speech».

Aggression is also manifested in the space used for sharing as the public one in which glass barriers divide society by class, social extraction, opportunities. In this artwork (“Glass frontiers”) we realize how decisions made by institutions, often based on data, can affect the lives of individuals. There is always a need for a responsible subject, one cannot hide behind an algorithm».

It is precisely the algorithms that are put at the center of the reflection in “Data violence”. As soon as the viewer approaches the surveillance cameras planted on the wall, he is detected and filed by the algorithm within seconds.

In a society where computers perform an ever-increasing number of tasks for us, we need to be aware of the interests behind the data we interact with. In “Selfie dysmorphia” is shown all the power that algorithms can exert on our psyche, up to destroy the very image that we have of us, continuously distorted, crippled, violated, until the moment when we consider the face reflected in the mirror as alien. «The mechanisms behind social networks are designed to keep us attached to the screen for as long as possible», says the founder of DDS, who stresses that «no algorithm is neutral, we cannot claim that it is because it is created by man. There is no human creation that is not influenced by interests, as well as cultural prejudices and cognitive biases. Even behind the construction of a chair there are values that indicate how to interact with that portion of space».

The shape, as well as the color of the chairs, is the vehicle of a message. The work “Hostile architecture” shows different types of seats that can be found in the city and on which, actually, it is impossible to sit: they are designed to discourage homeless people to rest, even if for a few hours, in places themselves intended for sharing, but in which their presence is unwanted. The vision of misery activates in the other a memory of their own fragility, as well as triggering an annoying sense of guilt, able to disturb the race towards the goal of everyone’s life: happiness.

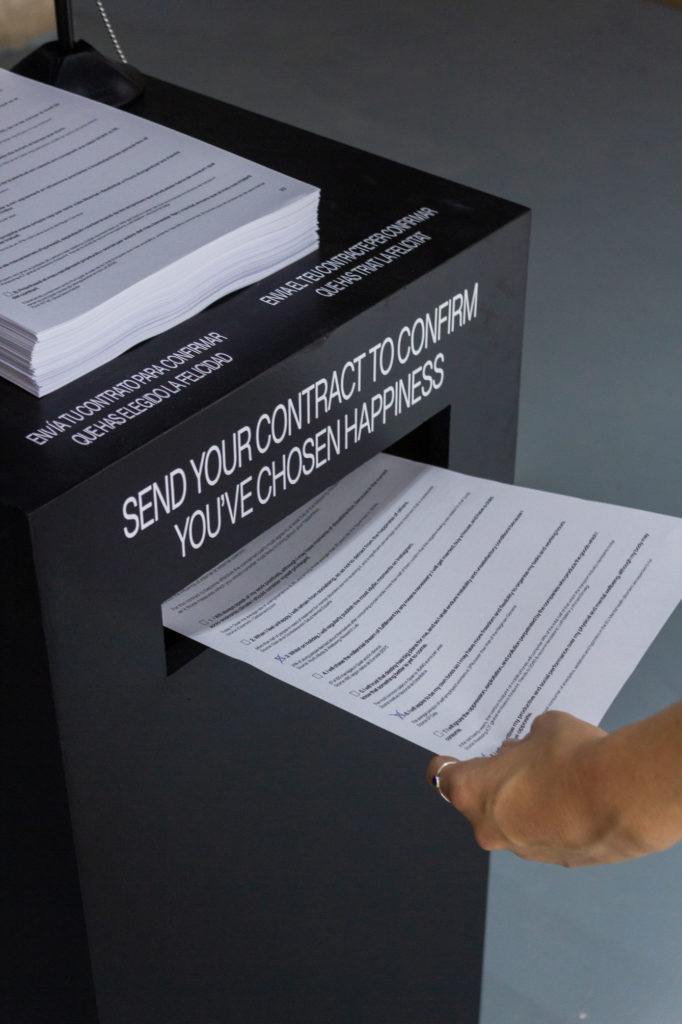

The final, most subtle and silent form of violence is hidden in the “happycracy” that feeds on the imperious sense of dissatisfaction that stimulates the accumulative frenzy typical of capitalism. «In “Happy violence” we invited visitors to sign a contract with which they undertook to be happy». Happiness, in its different forms, is the only acceptable emotion and one of the clauses says “when I feel sad I will avoid socializing so that people around me are not influenced by my bad mood”.

Indifference is the last form of violence explored in the 730 hours: a comfortable bed that welcomes us, with warm white blankets with red prints composing a phrase: “about 540 people are evicted from their homes every month in Barcelona”. These are the data that emerged thanks to the collaboration with activists and non-profit associations. – says Pau Garcia – . We talk about 60 people a day who lose their home. What their neighbors will do is, likely, nothing».

The dulling felt just before falling asleep is the same as in this last installation, which refers to the concept of “Statistical numbing” developed by the American psychologist Paul Slovic. Whenever we have been exposed to a great deal of violence – continues Garcia – our senses are anesthetized, it is something that belongs to our brain, it is a mechanism that allows us to survive. It’s happening now, too, with the war in Ukraine. It will take some time before we recover the ability to suffer the impact of the images we are seeing. I do not think it is wrong to look at the atrocities of the conflict, they allow us to better understand what is happening. What we see today is nothing new, we have already seen atrocious images of the Holocaust, of the genocide in Rwanda, of Syrian refugees, of the bodies of migrants lying on our beaches. Like the other times, the horror aroused by the brutal gestures of man will return, perhaps together with a new awareness of how much violence is hidden behind daily gestures».