The myth of uncontrolled has been overpopulation debunked. The end-of-century challenge will be declining birth rates, in Europe as well as Africa

The images of African families with as many children as players in a football team belong to the past. The country with the highest birth rate remains Niger, where each woman of childbearing age completes an average of six pregnancies. However, even here, the birth rate has decreased by almost two units compared to the values at the end of the 20th century. A shocking study by The Lancet predicts a collapse in the total fertility rate (TFR) in 97% of countries: by 2100, only six nations will have a positive natural balance. Thus, the fear of exponential and limitless growth is unfounded: the world’s population will peak in the second half of the 21st century, before contracting inexorably.

The effects of decline will not be visible everywhere at the same time. The Global South still has decades of demographic boom ahead before joining the West in a steep decline: enough to deeply change the face of the planet as we know it. By the end of the century, Nigeria will become the third most populous country, with over 540 million inhabitants: 80 million just in the capital, Lagos. India, which recently surpassed China, will continue to lead the ranking, with a billion and a half people: Mumbai and Delhi, two ant farms with over 50 million citizens. Other megacities will spring up like mushrooms, and lesser-known African capitals will rank in the top positions, overturning current references: New York or London will slip to 22nd and 86th place, supplanted by the new giants. This is the scenario predicted by American scholars Daniel Hoornweg and Kevin Pope, based on ongoing demographic trends. It’s a revolution of global balances in which our latitudes will play no role.

Europe is the only continent set to experience a net population decline by 2100. A deficit of twenty million is projected, unless there are migratory flows due to wars, climate change, and other unpredictable variables that Eurostat sources define as “difficult to quantify in a mathematical model.”

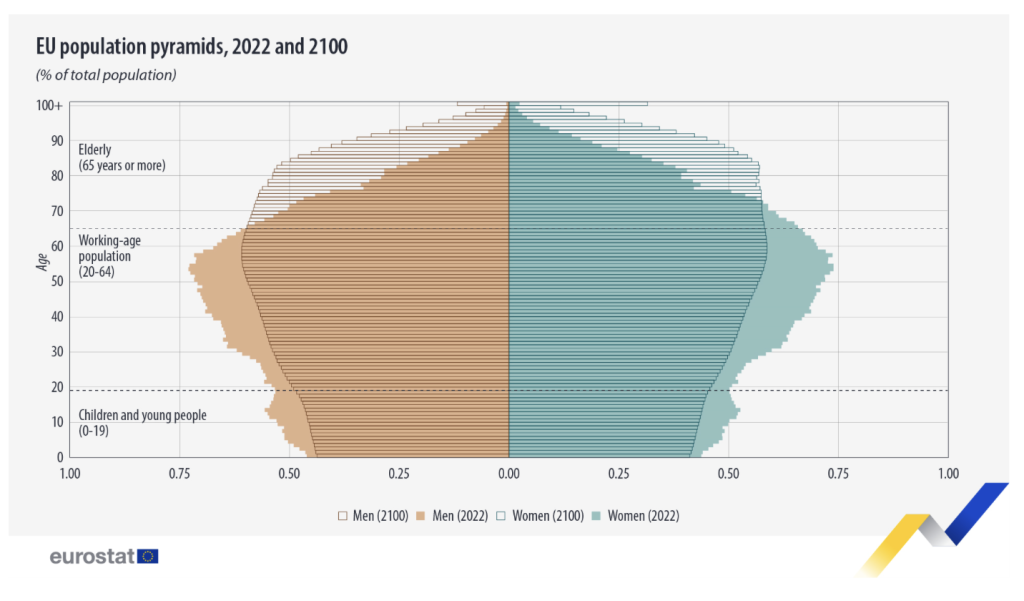

It’s not so the population contraction that worries the most, but the consequent demographic shift. The Old Continent, old in name and in fact, is already heading towards a progressive increase in the average age: what was once called the age pyramid now resembles a diamond, with its shorter diagonal sliding higher on the Y axis each year.

Professor Alessandro Rosina, a lecturer in Demography and Social Statistics at the Catholic University of Milan, describes the phenomenon with a neologism: dejuvenation. By 2100, citizens over 70 will be as numerous as those in the 18-69 age group. In other words, for every European in the productive phase, there will be a pensioner to support.

“It’s the inevitable consequence of medical-scientific progress,” explains Professor Rosina. “We have chosen to defeat premature death and live longer. The challenge is to ensure that longevity is accompanied by an improvement in the quality of life. The problem doesn’t concern only the pension system: in addition to pensions, we must guarantee care and assistance for the elderly, and to do so, we need doctors, nurses, drivers, and social workers. We need wealth and workforce, which will be increasingly difficult to find if the active population continues to contract due to dejuvenation.”

The issue is more complex than we imagine: “A society in which welfare cannot be guaranteed for all is difficult to govern. The older age groups, whose rights are not protected, will vote to defend their interests, creating divisions with the rest of the electorate.”

For the professor, there is no single remedy but a cocktail of possible solutions: “We have various models to emulate. Japan has decided to focus entirely on automation and robotics to increase the productivity of a declining population, but has done little on the fronts of female employment and immigration.” Other countries are encouraging migration flows, exploiting the resource to their advantage. “In Italy, the debate on the issue is limited to security aspects: we haven’t figured out how to incentivize ‘quality’ immigration, channeling qualified labor through the right channels to produce wealth.”

However, all these measures represent “patches” to the problem and not a long-term solution: “To combat the birth rate crisis, we need to ensure that young people start having children again,” continues the professor. “It’s difficult to plan a pregnancy when you’re thirty and still living with your parents: sometimes not having children becomes a forced decision.”

In our country, the birth rate crisis is also supported by a progressive desertification, the result of decades of wrong policies: “Ambitious young people increasingly often move abroad to build their future. It’s not just a career-related choice: today’s twenty- and thirty-year-olds dream of living in dynamic realities. They want to be at the center of change and take part in it.” A promising job perspective is not enough: what makes a city and a nation appealing are the protection of civil rights, services, and the cultural scene. “Preventing young people from packing their bags and attracting new ones is the biggest investment that can be made to stem demographic decline and be competitive in the future.” Looking at Eurostat statistics, it is evident that some countries are doing better than others: metropolitan areas like Madrid and Barcelona are experiencing sustained growth and will gain some million inhabitants by the end of the decade.

It will be the most stimulating urban areas that will defend themselves from depopulation over the course of the century, even in our country. It is impossible to predict what Italy’s demography will be like in 75 years. However, the professor does not expect any big surprises: “Northern Italy should confirm itself as the most populous area. Milan, Naples, and Rome will continue to be the most important hubs, around which millions of people will gravitate.” Some growth prospects will be seen for provinces and rural areas well connected to the metropolises: “Many will decide to escape from the smog and traffic of the cities, but they won’t give up the possibility of reaching the center quickly.”

The South and the most remote rural areas, on the other hand, will be destined to empty out: isolation is disliked today and people will like it even less at the end of the century.