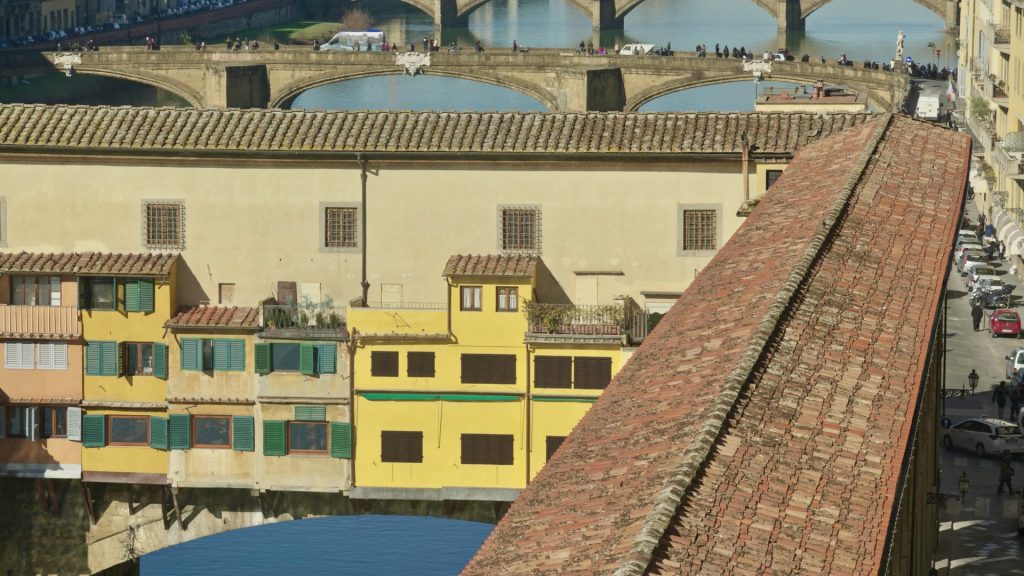

A private aerial passage, safe and unguarded, connecting the new family residence, Palazzo Pitti, to the seat of city government, Palazzo della Signoria. When Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici commissioned architect Giorgio Vasari in March 1565 to construct a 750-meter-long service “corridor,” he likely didn’t imagine that this passage would become a symbol of Florence. Nearly 500 years later, the Vasari Corridor continues to overlook the streets of the city center from above. Closed for the past eight years for restoration, it reopened to the public on December 21. Visitors can now explore it as part of the Uffizi Galleries with a special ticket costing €43.

Until 2016, the Corridor housed a rich collection of self-portraits, installed there in 1973. Today, it is bare, restored to its original state as it was when used by the ruling family. Visitors now enter through the Gallery of Statues and Paintings and exit through a small door near the Buontalenti Grotto in the Boboli Gardens.

A wedding gift that redeveloped the neighbourhood: what was the path for?

A pinnacle of the union between art and power, the Vasari Corridor was born as a wedding gift. “Cosimo I was preparing to celebrate the marriage of his son Francesco I to Archduchess Joanna of Austria, a politically significant arranged marriage to strengthen ties with the Habsburgs,” explains Simona Pasquinucci, head of the curatorial division at the Uffizi Galleries. “The Medici had recently purchased Palazzo Pitti (in 1549) to make it their new family residence, and Cosimo wanted it connected to Palazzo della Signoria via an elevated tunnel. Vasari, his trusted architect, completed it in just a few months, in time for the wedding on December 18, 1565.”

Initially known as the “Pathway of the Prince,” the structure was a lightweight, elegant design meant to impress the Habsburg guests. “It was a major urban project for Florence,” Pasquinucci continues. “The construction of the corridor prompted the redevelopment, as we’d call it today, of a cramped area filled with shanties and activities reliant on the river. The Loggia del Pesce had recently been completed and was relocated to the old market area.” Thanks to Vasari’s project, the Medici family could move with great convenience without setting foot on the streets. This spared them the risks of attacks, contracting illnesses, and even the unpleasant smell of pork from the butchers’ shops on Ponte Vecchio.

The Family That Resisted: The Story of the Mannelli Tower, dear to Oriana Fallaci

The Corridor had to be completed quickly, so it was built on pre-existing structures: from the Uffizi construction site—then housing government magistrates rather than a museum—to Palazzo Pitti, passing over Ponte Vecchio. The tower houses along the route, at least their upper floors, were requisitioned, with the exception of the Mannelli Tower, owned by an ancient family hostile to the Medici rulers. “Vasari devised a way to bypass the tower from the outside,” explains Pasquinucci. He used a refined system of corbels—stone supports—that keep the structure suspended, creating the impression of an embrace.

During World War II, the Mannelli Tower gained new fame as the headquarters of the Resistance. It was the place where Florentine journalist Oriana Fallaci wished to die, as she declared, because as a child, she used it to collect weapons and explosives for her father, Edoardo, commander of the Giustizia e Libertà Brigades.

The tribune in the church of Santa Felicita and the illustrious visitors of the 20th century

The Corridor leaves behind the Arno, penetrates buildings, and re-emerges at the facade of Santa Felicita Church. Its loggia overlooks the interior, where a gallery allowed the Medici to follow religious services from a privileged position. Over the centuries, the Corridor has maintained its precious role as a passageway. “Even today, we use it to transport artworks from one location to another; it’s incredibly convenient!” concludes Pasquinucci.

Many illustrious figures have walked through it: “Prime Minister Giovanni Spadolini, founder of the Ministry of Cultural Heritage, the painter Marc Chagall when he donated his self-portrait, the royal families of England, Denmark, and many others. All have contributed to the regal and exclusive image of this aerial pathway, a sort of elite salon made all the more alluring by its difficult access. From now on, it will be easier for everyone to admire it, but we are confident the Corridor will retain its extraordinary allure.”

Read also: Christmas Markets, a long-standing tradition in Germany