For the first time in recent history, English is no longer the undisputed star of the Eurovision Song Contest. In 2025, more than half of the participating countries have chosen to perform in their native languages, breaking a trend that has dominated the competition for over two decades.

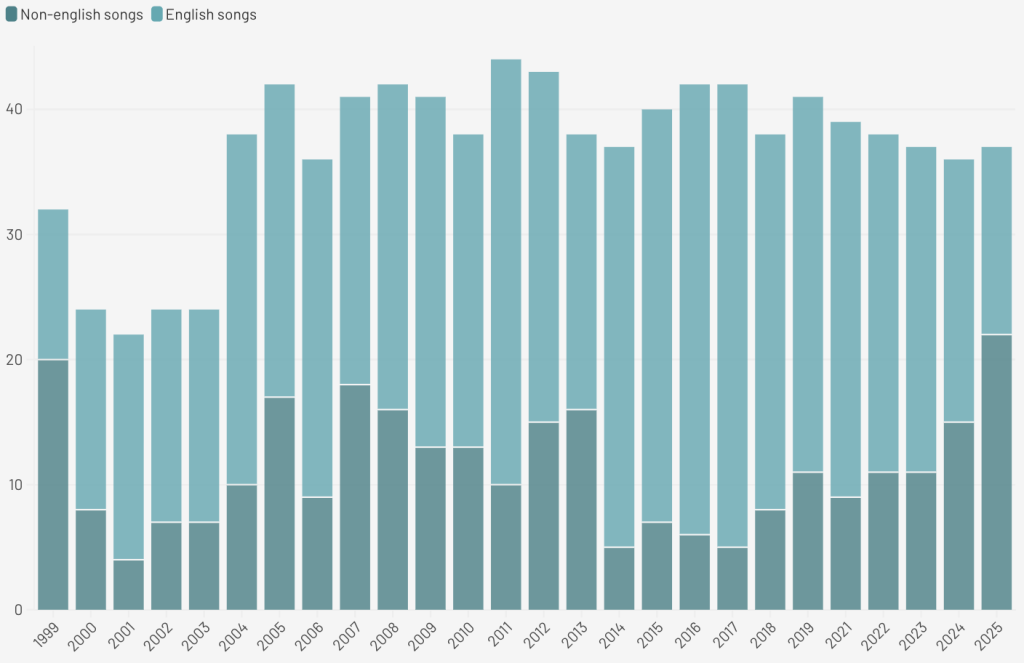

Since 1999, when Eurovision lifted the requirement for artists to sing in their national languages, the contest has leaned heavily toward English. The language became the safest bet—a universal key to international success and instant comprehension. Fearing they wouldn’t connect with audiences, many artists set aside their linguistic roots in favor of a more globalized pop sound, designed to appeal to the widest possible audience.

A shift in the spotlight

This year, however, tells a different story. Germany is returning to German for the first time in 18 years with Baller. Sweden, a powerhouse in the competition, is singing in Swedish for the first time since 1998 with Bada Bara Batsu.

This shift is not a coincidence, nor is it an isolated event. The trend began in 2017, when Portugal’s Salvador Sobral won with Amar pelos dois, a ballad inspired by traditional fado music. His victory cracked Eurovision’s English-dominated façade, proving that emotional depth and cultural identity could transcend language barriers.

Since then, more artists have followed suit. In 2021, Italy’s Måneskin won with Zitti e Buoni, a high-energy rock anthem in Italian. The following year, Ukraine’s Kalush Orchestra triumphed with Stefania, a song in Ukrainian that became a symbol of national resilience. Each of these victories demonstrated that while English-language pop remains popular, there is also a growing demand for performances that embrace distinct cultural identities. Even countries that once stuck to English have begun experimenting, enriching the contest with a broader range of languages and styles.

Eurovision: a stage for both global pop and national identity

The return to native languages is more than just a musical choice. Increasingly, countries see Eurovision not only as a showcase for international pop but also as an opportunity to reaffirm their cultural identity.

Latvia’s entry this year, Bur man laimi by Tautumeitas, blends Baltic folk sounds with contemporary pop. Lithuania, following the success of Luktelk, has once again chosen a song in Lithuanian, Tavo akys. Eurovision 2025 continues to deliver the high-energy pop designed for a broad audience, but it now also features a mosaic of songs deeply rooted in national heritage.

For decades, English has served as Eurovision’s lingua franca, a kind of neutral currency in Europe’s musical marketplace. But today, it no longer seems essential for success. A striking example of this shift is Europapa by Joost Klein, a quirky, surreal song in Dutch that has racked up over 170 million streams on Spotify. Despite—or perhaps because of—its playful lyrics and distinctly local flavor, the song has resonated with audiences across Europe.

In an era where the emotional connection between artist and audience matters more than the language itself, English is no longer the default—it’s just one option among many.