For the first time since the Unification of Italy, in 2022 births in our country fell below four hundred thousand. In the latest report from the National Institute of Statistics (Istat), just 393,000 births were recorded, seven thousand fewer than in 2021 and a staggering 183,000 less than in 2008, when the highest value of the 2000s was reported (576,659). Estimates for the first six months of 2023 show a further decline of 3,500 newborns. The total fertility rate (TFR), the index that measures the average number of children per woman, was 1.24 two years ago, the third lowest in Europe, and is now at 1.22.

This decrease is mainly due to the limited availability of women of reproductive age: today’s thirty-year-olds were born in the mid-1990s, at the peak of the so-called “baby bust,” the forty-year phase of declining fertility rates, which reached its lowest point in1995 at 1.19. The subsequent recovery between 2002 and 2008, which demographers call the “baby bounce,” was largely due to the contribution of foreigners. In recent years, this contribution has also diminished, as clarified by Maria Rita Testa, a demography professor at Luiss Guido Carli University in Rome: “Since 2019, the fertility of Italian women has remained unchanged at 1.18 children per woman, while that of immigrants was close to 2 and has dropped to 1.87.” Those who come to Italy, even from countries with very high birth rates, adapt to the socio-economic context and encounter the same difficulties as natives in balancing childcare and careers.

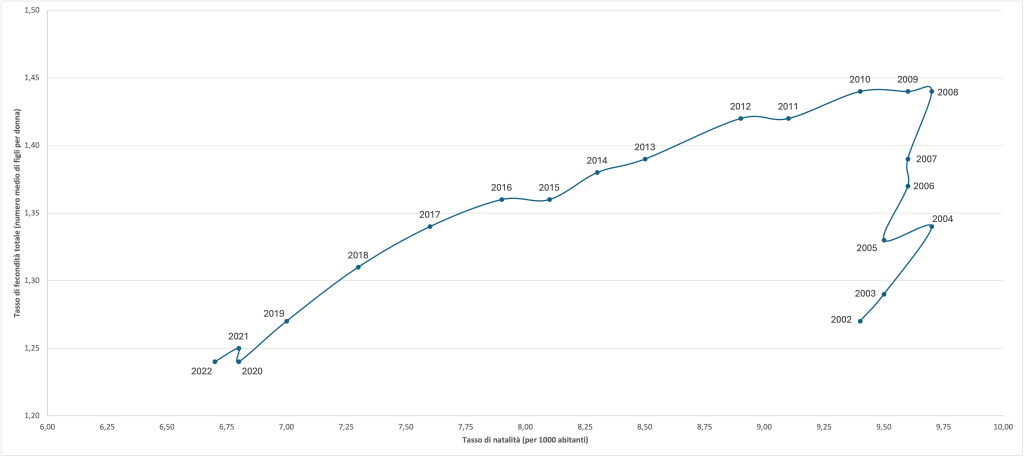

The reversal of the trend in the 2010s is clearly shown by the graph above, which correlates the total fertility rate of residents with the birth rate, i.e., the ratio of the number of births in a year to the population average, multiplied by a thousand. The peak of 2008 is followed by a continuous decrease in both indicators, with the curve declining to worrying levels in recent years. Behind the decline in births in Italy there is also the spread of post-modern values, which began in Europe in the 1980s and led to a continuous and gradual postponement of motherhood. This delay has been partially offset by an increase in fertility outside of marriage in Nordic countries, while in Italy, it has only grown in the last two decades: in 1995, births from unmarried couples were 8% of the total, today they are 41.5%, yet birth rates continue to decline. “One explanation lies in the still very marked gender differences,” says Testa. In addition to the wide gap in employment rates – the female rate is 55%, fourteen percentage points below the EU average, while the male rate is 75% – a different distribution of tasks within couples still takes place: women are the ones who are primarily responsible for household chores and childcare. Moreover, the shift in values is occurring in an unfavorable economic situation. Economic stagnation is compounded by the uncertainty caused by wars and “climate anxiety,” the worry about climate change, which particularly affects the younger generations.

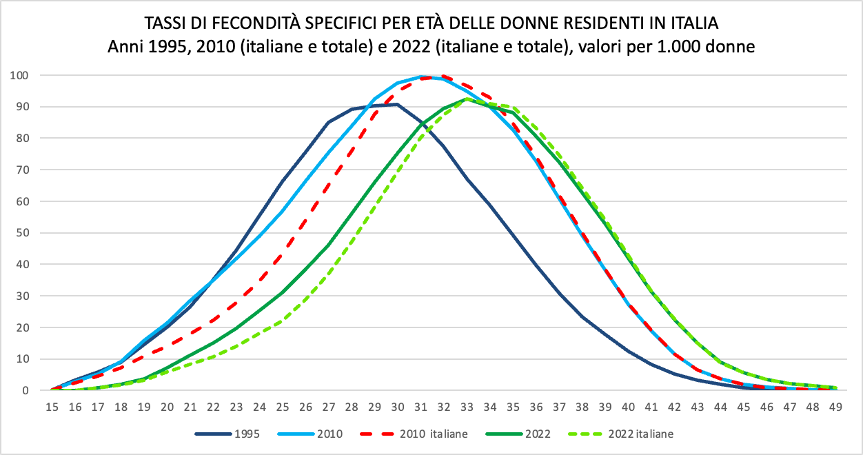

Demography is characterized by strong inertia; from one year to the next one, the change seems little, but in the long run, the effects are devastating: in sixty years, Italy has lost 60%of its births. Among the causes there is also the postponement of the average age at child birth. The Istat graph below, with specific fertility rates by age of women in 1995, 2010, and 2022, speaks volumes: nineteen years ago, the value was slightly below thirty years old, while in the latest survey, it is 32.4, higher for Italians (32.9) than for foreigners (29.6).

The worrying data is not only the decline in the population, which fell below sixty million for the first time in 2023, but the significant aging that results from it. For every 100 young people, there are now 184 elderly. Gustavo De Santis, a demography professor at theUniversity of Political Sciences “Cesare Alfieri” in Florence, states: “The age pyramid has been overturned for some time: the base, made up of new generations, is very narrow, while the top, formed by the cohorts of over-sixty-five-year-olds, will continue to widen. “The downward trend in births has worrying implications for the economy and the pension system. Possible remedies are unpopular with public opinion.” Working longer, lowering pensions, or opening the doors to immigration are unpopular solutions,” De Santis continues. Furthermore, foreigners would not be enough to improve the situation, for two reasons. The first is that they are selective:on average they have fewer children than their compatriots who stay in their home country. The second is that often Italy is just a temporary stop for them: “They come to find work, but after saving some money, they return home,” explains the professor.

For Italian women, the gap between reproductive intentions and achievements is also increasingly pronounced: they desire two children, but more and more often they only have one. It’s the “fertility gap,” which if confirmed over time could result in the trap of low fertility, theorized by Professor Testa: “If births were to remain below the replacement level of two births per woman for a long time,” she explains, “couples would adopt the one-child family model as a reference. The changing ambitions of the younger generations would push the fertility curve even lower, triggering an irreversible vicious cycle.”

Faced with this crisis, it is essential to consider policies capable of reversing the trend.”Continuous, flexible, and differentiated policy packages are needed, such as those adopted by Northern European countries,” says the demographer. For them to produce tangible effects, they must last at least thirty years and target not only women but also young couples. Germany has focused on work-family reconciliation: maternity and paternity leave combined with easier access to childcare. The Scandinavian countries have pursued gender equality, and from France, we can imitate the variety of support. “I would call it a systemic approach, which goes beyond family policy boundaries,” concludes Testa.” A non-demographic solution to the birth crisis is needed.”

Read also: The new Zeta magazine is out! Browse through it here