A drug circulates in America that kills more young adults aged 18 to 45 than car accidents, cancer, or cardiovascular diseases. Among the thousands of victims, there are even those who haven’t still reached adulthood and never will, like Adrian Lopez, known as Pancho, who was just fifteen. His only mistake was accepting a pill from strangers at a house party when he was already drunk. His best friend remembers his contagious smile.

There’s Jessica, 12 years old, a lively, athletic girl, and a volleyball lover. Her first and only dose seals her fate: she will never realize her dream of training with a professional team and preparing for the Olympics.

There’s Kristofer, one year and eleven months old. They find him lifeless, ten days before his second birthday, with bluish face and lips. His mother and her partner were smoking fentanyl on the couch just meters away from him. Forty-eight hours later, social services would have taken him away from that house, alerted by his biological father.

These are just three of the hundreds of victims to whom the Instagram community founded by activist Jeremy Kelsay strives to give a face and a name, dedicating a one-minute video reel to each, a final act of love from friends and family. The format is always the same: a sequence of photos and videos of happy moments, introduced by a bitter heading, “dear fentanyl.” In the closing, the emoji of an eagle and the words “Forever,” followed by the years the young people were at the time of death.

The page is called “Every 11 minutes“: sadly, the number “eleven” most likely underestimates the frequency of deaths.

For an American, losing a friend or family member to overdose is a common tragedy. An Italian, on the other hand, struggles to grasp the magnitude of the tragedy. Scrolling through the community feed, we can’t understand how so many teenagers, children, and even babies can be killed by a substance we barely know, and that almost no one had heard of until a few weeks ago, when Meloni’s government launched a prevention plan.

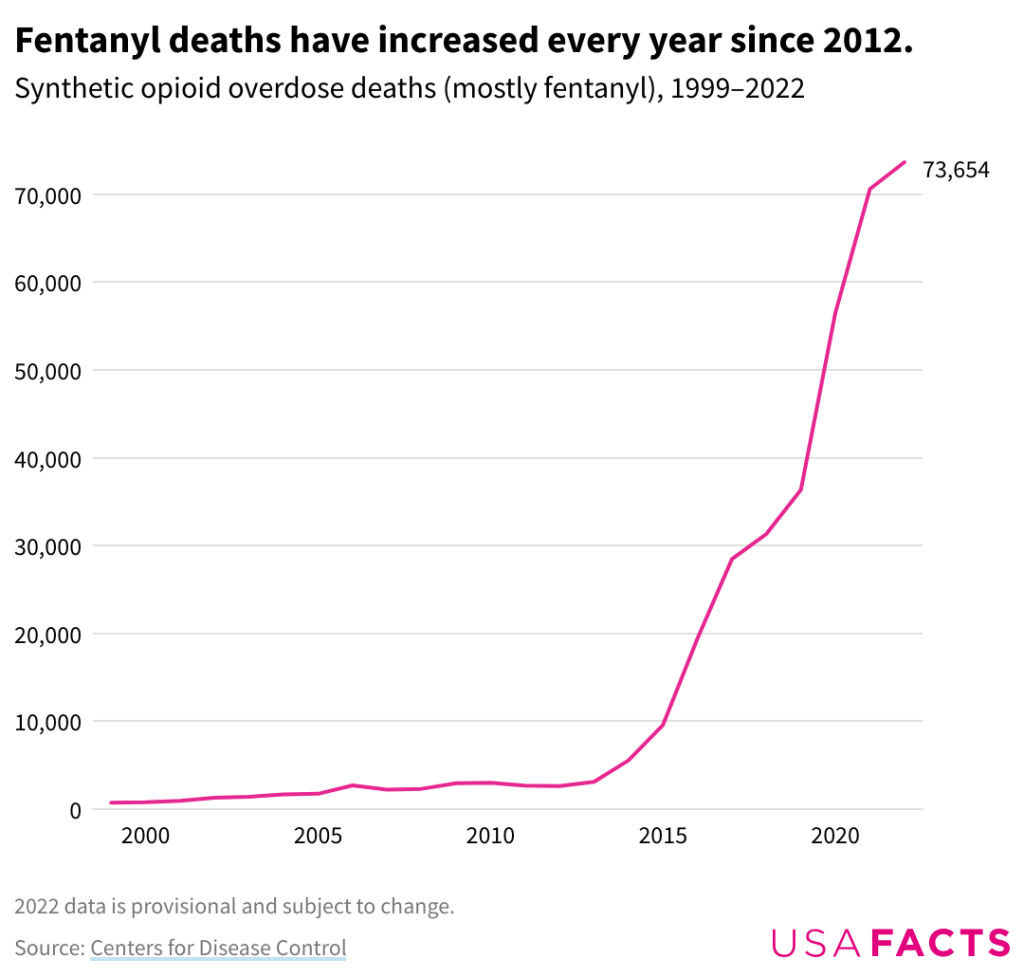

Fentanyl belongs to the class of synthetic opioids: it is a drug produced in the laboratory but with a mechanism of action similar to that of opium and its natural derivatives. Used as an anesthetic and analgesic in the treatment of chronic pain, it is fifty times more potent than heroin. Like heroin, it is associated with addiction and risk of overdose, with a lethal dose of only 2 mg (pictured below: comparison between a fatal dose and a coin). To get a clearer picture, one kilogram of fentanyl would be enough to kill the entire continent of Europe. In the United States, hundreds of thousands of lives have already been cut short in the past decade. More than 70,000 deaths in 2022 alone.

In Europe’s ignorance, on the other side of the ocean, the emergency began in 2016, with the start of the fourth wave of the opioid epidemic. There are precedents in recent US history: the mid-1990s saw a spike in heroin use, but according to data from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, it was oxycodone that played the main role in the first wave (1999-mid-2000).

Marketed under the name OxyContin by the pharmaceutical company Purdue Pharma, the semisynthetic opioid promised the same benefits as morphine, without the attached risk of addiction. A massive marketing campaign began, with an army of young salesmen and saleswomen deployed in every county: the goal was to convince doctors to prescribe as many pills as possible. Depending on the number of prescriptions signed, various prizes and benefits were offered. Years later, it was discovered that the company was aware of the dangers of the substance but buried the evidence to avoid scandal.

In 2007, Purdue Pharma was forced to pay a fine of $600 million for the use of deceptive practices. The case became a media sensation, well documented by the Netflix series “Painkiller”.

By the 2010s, hundreds of thousands of Americans were addicted to opioids: fertile ground for a second wave led by heroin. It is with fentanyl, however, that the curve becomes a steep slope: after a third wave sustained by prescription drugs alone, a fourth, extremely powerful crisis arrives, in which the main player is the black market. Mexican cartels begin to produce the drug in industrial quantities with no compliance with pharmacological doses. They flood the United States with pills containing more opioid than the lethal dose. In an effort to diversify and expand the market, they also begin to mix fentanyl with amphetamines and stimulants, with contradictory and devastating effects on the cardiovascular system.

Two consumer profiles begin to emerge. The classic prototype is represented by former heroin addicts who flock to the sidewalks of Philadelphia, Los Angeles, San Francisco: by their posture and walk they look like zombies. Then there are ordinary, middle-class citizens: young people and adolescents who come into contact with the substance at nightclubs or house parties. For many of them, it is their first approach with the world of drugs. Some even consume fentanyl unwittingly, dissolved in a drink or cut with other party drugs.

The magazine Rolling Stone has described the opioid epidemic as “a uniquely American problem.” There are several possible reasons why the crisis has not yet replicated itself in Europe: geographical distance from drug cartels, stricter rules regarding medical prescriptions, and a different social and economic fabric. According to data from the National Health Institute (Istituto Europeo di Sanità, ISS), fentanyl overdose deaths in Italy from 2016 to date would be only two.

That could soon change: on March 12, Undersecretary to the Prime Minister Alfredo Mantovano announced a prevention plan to counter the misuse of the opioid and its entry onto the black market. Intelligence services reportedly intercepted an ‘Ndrangheta interest in the substance. Since then, reports have multiplied: on March 24, the Giornale di Vicenza wrote of an increase in suspicious overdoses at the San Bortolo Hospital, news soon denied by the spokesperson for the Aulss 8. The ISS press office confirmed, however, the discovery of a dose of heroin cut with the opioid in the province of Perugia: “It is the first time this has happened in our analysis laboratories.”

The threat of fentanyl is much more concrete than a “POSITIVE” written on a white sheet of paper.

At the R5 in Tor Bella Monaca, the nerve center of Roman drug trafficking, it takes five seconds and 25 euros to buy a pill, that comes in an anonymous red blister pack with no markings. The drug that has killed hundreds of thousands of Americans is already here, in the outskirts of our cities, and perhaps we are not prepared enough to face it.