Italians are having fewer children, the average age at the birth of the first child is increasingly higher, and low fertility is one of the most addressed issues in politics. Comparisons with other European countries make the anomaly even more evident, but also provide interesting insights into what the most effective remedies are to counter the birth rate crisis.

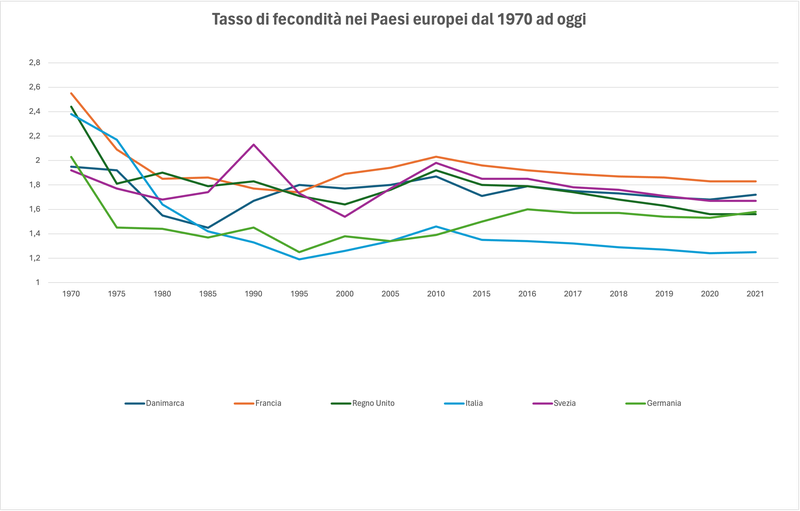

The main statistical indicator for comparing the birth rate of different populations is the fertility rate, which measures the average number of children per woman. When rates lower than 1.3 children per woman were first observed in the early 1990s, demographers were prompted to use a new category to indicate this trend: lowest-low fertility. Since then, most European countries have managed to recover and now stand at averages above that threshold. Italy is an exception.

The drastic decline in newborns since the 1970s has affected the whole of Europe and is associated with the massive entry of women into the labor market. It marks the end of the male breadwinner model, in which the male head of the household was responsible for providing economic support, while women were assigned domestic work. The end of role specialization within families has not undergone the same transition everywhere.

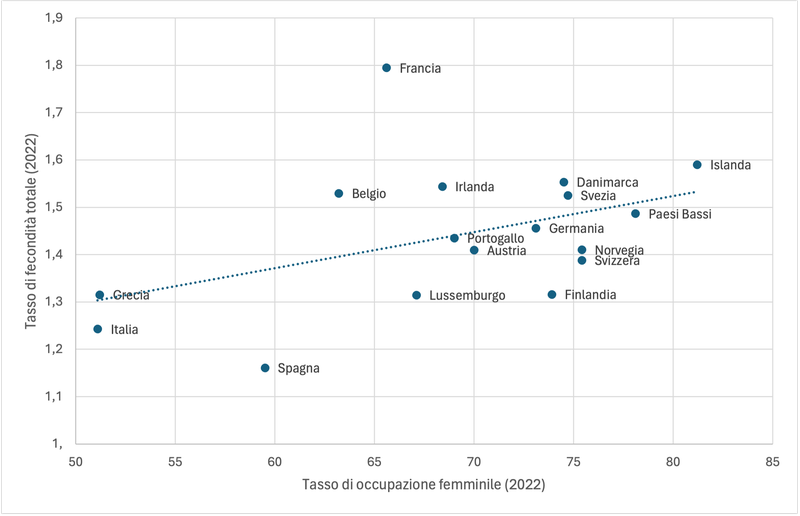

Patriarchal legacy and the perpetuation of traditional social norms have often forced women to shoulder a double burden: alongside household care work, there’s been wage employment. Today, higher fertility rates are found in egalitarian countries and are associated with a higher degree of well-being and the presence of a welfare state that allows for the reconciliation of family and work life.

Data suggests that moving away from the traditional model is necessary for larger families. Equal division of domestic labor and policies supporting female employment play a crucial role.

The idea of the career-oriented woman who prioritizes work over family is a stereotype unsupported by numbers. In the absence of adequate public structures, an increasing number of middle- to high-income families can afford to outsource family care work.

While not having children remains a difficult social stigma for Italian women to endure, having them has become a class privilege. The consequences of that fall on social mobility, the stability of the pension system, and, above all, intergenerational equity. An aging country leaves less and less room for young people to decide their future. Demography and democracy can collide, and with a slim electoral weight, it will be difficult to give relevance to generational issues such as the climate crisis.

Migrations are often identified as a possible remedy to society’s aging, however, the impact on birth rates is increasingly limited. The average number of children per foreign woman in Italy has decreased from 2.79 in 2007 to 1.87 in 202. With almost one child less in just fourteen years, foreign families have quickly adapted to the reproductive habits of Italian ones.

No effect is guaranteed, and even Scandinavian countries have experienced a contraction in fertility in recent years. However, the good news is that empty cradles are not an inevitable fate. It requires a new way of looking at social roles within families and targeted public policies. Observing the initial birth rate crisis and subsequent recovery in countries with fewer inequalities between women and men, some demographers have spoken of a two-part gender revolution. This as well won’t be a dinner party, and this time, dads will have to help clear the table.

Read also: https://zetaluiss.it/2024/03/27/nascita-zeta-marzo/